You are currently browsing the monthly archive for April 2013.

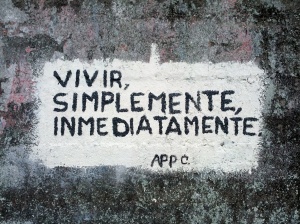

My first impressions of Quito weren’t that great, I admit. However, after being admonished by several friends who had loved the city, I decided to put my first thoughts aside and focus on getting a feeling for the city instead. After spending a week running errands and sightseeing in Quito’s core, I’ve come to appreciate the place a lot more than I expected.

Quito feels very big, both in geography and population. I was staying far outside of town, and the buses into the Centro Historico were regularly packed, and often delayed by traffic where they didn’t have dedicated lanes. The buses felt very safe, though – even pressed into the throng of people, I didn’t fear for my wallet. Most of the time when I was standing, men would offer me their seats. Moments later, I had to give them up for mothers or fathers carrying infants, retirees, or young men with their limbs in casts, but over the course of one hour-long bus ride, I was offered at least six people’s seats. Considering the men offered me their seats without the usual pick-up line, I was doubly impressed.

Getting off the bus in the historical centre was an assault on the senses. Hundreds of people were going this way and that, selling, buying, and calling out to passersby. Dozens of women in traditional dress moved through the crowd, with bags of apples, avocados, mandarin oranges, grapes, and more kinds of local fruit than I could name. Their high-pitched sales calls reminded me of auctioneers, imploring us at piercing levels to buy their wares. “Mandarina, mandarina, un dollar, un dollar, mandarina un dollar, mandarina un dollar!” Vendors were everywhere, selling ice cream, gum, coca leaves, phone cards, jackets, coffee filters, TV antennas, anything you could imagine. None of the sales pitches were aggressive, though – I felt free to wander the area without buying anything.

Walking up the hill toward the main square of the Centro Historico, it occurred to me that I had been spoiled by beautiful cities in Colombia. The historical buildings in Quito were interspersed with concrete block monstrosities that ruined the effect for me. I had also come to expect window boxes bursting with colourful blossoms, and I wasn’t appreciating the architecture nearly as much without them. In places, though, I was stunned by the beauty surrounding me. Many grand buildings like churches used intense green roofing tiles – I couldn’t tell if they were some kind of stone or ceramic tiles finished in a deep green glaze.

While I was pulling out my phone to take a picture of one building’s incredible roof, a man in a yellow shirt stopped in his tracks, and then made a beeline for me. I looked at him, and he immediately pretended to be interested in something on the ground. I turned back to my photo, and he tried to sidle up behind me. I moved about ten feet away from him, and he started wandering in my direction, innocently looking at something else. I wasn’t sure if he was trying to pickpocket me, rob me, or do a snatch-and-run theft of my phone, but luckily his approach was unsubtle enough that I was able to get the heck out of there before he did.

I hadn’t planned to do anything particularly touristy, but ended up having a few extra hours to kill, so I walked up to the Basilica at the top of the hill. I had seen its towers from almost every corner of the city, but hadn’t realized just how huge it was! I spent almost an hour wandering around the outside of the building, trying to capture its scale and grandeur in a photograph. I came close, but I think the task was impossible.

There was less than an hour left before closing when I finally bought my ticket to go inside. (Worshippers can enter for free, but aren’t allowed to climb the cathedral’s towers and view the city below.) The second story was lit by incredible stained glass windows, full of bright images of flowers amongst the saints. There was a huge pipe organ in the corner, but the hymns echoing through the stone columns must have been coming from somewhere else. They were lovely to hear nonetheless.

With every step I took, the building became more amazing. Peepholes in the stone staircases gave glimpses of gargoyles in the shape of local birds and wildlife. I stepped out at the top to see the lookout over the city below. It was high. Cars looked like tinkertoys, and people were the size of ants. The sound of hymns from the worshippers had receded and was replaced with the far-off noise of traffic, barking dogs, and car horns. I was alone at the top of the wall, and it felt like I was miles above everyone else in the world. I looked over at another incredible tower on the other side of the church, where dozens of people were snapping pictures, but decided not to go there. Instead, I got tempted by a tiny sign pointing to a winding metal stair – “clock tower and belfry”.

I’ll admit here, I’m not comfortable with heights. The tiny staircase kept going up and up, six revolutions of white-knuckle climbing, gripping my bag in one hand and the rail in the other, as if my life depended on it. The ticking of the giant clock felt like the ominous soundtrack to my climb, drowning out every noise but the sound of my footsteps on the winding metal stair. And then, I reached the top and looked down. The only way I could think to describe it was “ass-clenching”. As I took a couple of pictures, I noticed it was time for the church to be closing. I gratefully retreated to solid ground, although I was proud of myself for making it to the top.

On the way back to the bus, the street was echoing with the sounds of rhythmic chanting and singing. A capoeira class was in progress in an open studio, and dozens of young men sat in a circle, keeping the beat while watching two black teenagers spinning and twirling in mock battle. A blond woman sat apart from the group, camera at the ready. I thought about popping in, but it was going to be dark soon, and I had a long bus ride back to the suburbs.

Ellen and I have heard a lot about couchsurfing, and many broke long-term travellers recommend it highly. Until I got to Quito, though, neither of us had couchsurfed before. We’ve glanced a few times through potential hosts’ profiles, but so many of them read suspiciously like personals ads that we never bothered trying to find accommodation through the site. This week my feelings on the matter have changed after staying with a friend of Ingo’s who lives near the airport. Staying at someone’s house has some huge advantages over hostels!

The most obvious benefit of staying with a local is the financial savings. The cheapest hostel room I found was $8 a night (although I didn’t look far). Spending a week at Steve’s house saved me at least $50. Not only that, but I have the use of Steve’s kitchen, which is much better outfitted than a hostel’s shared kitchen, as well as a bathroom that I never have to line up for, and unlimited access to a washing machine that I don’t have to pay for. When you add up those benefits, I’ve probably saved at least another $20, especially on meals that I didn’t eat out.

Another huge advantage is having a local insider to give you directions and suggestions on places to go. Here I lucked out as well – Steve first came to Ecuador 40 years ago, and has plenty of information to help me get all my errands done. He doesn’t know as much about tourist sites, but his sister-in-law Dora who lives nearby has plenty of advice to offer me. My running around town has been much more pleasant than I expected, mostly because I can pick Steve and Dora’s brains on where to go.

Another sweet building that reminds me of Cartagena (fewer flowers, though – Cartagena still wins nicest city award!)

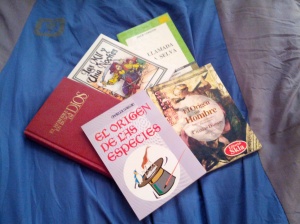

The best part of this couchsurfing experience, though, has to be feeling welcomed at somebody’s home, rather than like a tourist in a hostel. Steve has been an amazing host – when I mentioned that I was hoping to read more about natural building techniques, he brought out half a dozen books on the subject that I could browse through. His library on customizing WordPress has inspired me to play around with my blog more over the next few months, and we’ve been having animated conversations on all sorts of topics.

The absolute highlight, though, is that Steve is a distributor for the artisan brewery in Canoa whose beer Ellen and I tasted on our trip to the beach. The brews are only available by the keg, but Steve has a fridge full of bottled samples, of which he said I could help myself to two or three of each kind. That’s exactly what I’m planning on doing this afternoon, in a hammock in Steve’s beautiful garden, with my sketchbook on my lap and a steady supply of nice cold microbrew next to me. I can’t even remember – why was I unenthusiastic about couchsurfing again?

It’s been almost half a year since Ellen and I left for Latin America with little money in our pockets and no plans to speak of. We had ideas and vague intentions, but nothing concrete. As our trip has progressed, we’ve regularly felt grateful that we had themes to focus on rather than plans to stick to. Now, as Ellen is spending a few weeks in Canada getting her future sorted out, I figured I’d spend some time looking back on our vacation to see what we’ve done and what more I’d like to do. I’m not making a bucket list – I read an article that eloquently lays out reasons to avoid those – but I’m examining the themes of our travels over the past months and into the future.

- Working with Wildlife – We left home with this idea featuring prominently in our minds, but it hasn’t materialized yet. There are plenty of wildlife rescue places in Latin America, but most require volunteers to make a hefty donation to the centre in exchange for the opportunity to work with monkeys, snakes, turtles, or wildcats. Ellen might choose to pursue this further, but my budget has relegated this idea to the back burner for me.

- Beer – Every travel article I’ve read says there’s no good beer to speak of in Latin America. Ellen and I set out to prove them wrong by finding microbreweries and artisan beer on our trip. This focus of our travel has had mixed results. We didn’t search extensively in Costa Rica or Panama, but instead drank what the locals drank. We had more success once we hit South America. We found an excellent craft brewery in Medellin, Colombia, and were able to sample local beer from Bogota as well. In Ecuador, there’s good local beer to be found on tap in Canoa, and I also had the pleasure of buying the first two bottles of ginger beer brewed in Mindo. This week I’m couchsurfing at the home of an American who distributes the craft beers from Canoa, and who has asked me to help him close a couple of deals while I’m in Quito. I hope this will allow me to sample their India Pale Ale, which is my favourite type of beer and which I have sorely missed in Latin America. Ellen and I have also played with brewing our own beer at the farm here in Ecuador, as well as making traditional fruit alcohols in Costa Rica, Colombia, and Ecuador. I look forward to continuing to explore our passion for good beer as the trip carries on!

- Food – I absolutely love the food here. Ellen and I have enthusiastically embraced local ingredients and experimented with imitating Latin American dishes and incorporating the new fruits and vegetables into foods we like from home. I haven’t done as much exploration of the South American food culture as I’d like – I think I’d need to be living and working here so I could systematically make sure I’ve tried everything – but Ellen and I are eating fresh, local foods every day, so I would call this a rewarding focus of our trip.

- Writing – When I started my blog, I hoped to write almost every day. I wanted my blog to record my journey, capture my reactions to new experiences, and keep my friends and family informed of my movements. Beyond that, I also wanted my blog to serve as a portfolio of my writing style, an avenue for self-improvement through daily writing practice, and a venue to expand my contacts and open doors to a potential career in the writing or publishing industry. I haven’t written quite as much as I hoped, and spending time out of internet service has limited my ability to be actively promoting my blog and interacting with readers. However, I’m enjoying the project immensely, and Ellen appreciates being able to keep her network of friends informed without having to use the internet herself.

- Sketching and Painting – I haven’t been doing as much artwork as I’d hoped on my journey, but neither have I abandoned the hobby. I’ve been pleased to be able to improve my skills at sketching especially – I’m finding a style of my own that I like, and enjoying the process of drawing as well as the results. Painting I’ve found less rewarding, so I’m focusing more on my work with markers on paper. Maybe when I’m more settled in one place, I’ll experiment with the Asian black and white watercolour style that I’d like to someday emulate.

- Sustainability – I didn’t set out to learn what Latin America could teach me about conservation of resources, but it seems this lesson found me on its own. Everywhere I look, I’m struck by how the locals are doing things in ways that don’t create nearly as much waste as we would at home. Latin America still has pollution problems, waste management issues and a lack of recycling centres, but unnecessary packaging and wasteful lifestyles aren’t as endemic here. North Americans and Europeans are more aware of pollution as an issue, but Latin Americans seem more pragmatic about their consumption of resources.

- Natural Building – This new focus for my travels has surprised me. I’ve never been interested in architecture, but discovering how different natural resources like bamboo, straw, and clay can be put together to make comfortable houses that look and feel better than modern materials like concrete and drywall has been a rewarding pursuit. The more I see, the more excited about the subject I become. I am inspired to learn different natural building methods so I can eventually build a home myself. This has opened up all sorts of avenues of discovery to explore – I’m hoping to refresh my knowledge of electricity and wiring (my least favourite topic in high school physics) and learn about drainage and plumbing so I can understand how to construct a home from start to finish.

- Education – I had taken a hiatus from teaching when I started this trip – I felt disillusioned and tired of the whole industry. Taking a step back from my teaching career seems to have renewed my passion for learning, though. I’m excited about education again, brimming with ideas about teaching, learning, schooling, and exploring the world. I need more time to put my philosophy into words and understand how to apply it to my life, but the first steps are forming. I hope to incorporate these lessons into wherever my career takes me.

Travelling with a focus instead of definite plans has led me in exciting directions. Not only have I explored the themes I set out with, but I’ve discovered new passions on this trip. I still have no idea what my future holds or where I’ll be in six months, but at least I know what paths I might be interested in following.

After nearly six months of travelling with my sister, we’re splitting up. As I write this, Ellen is on a flight back to Saskatoon, where she’ll be for two weeks. Her plan is to go home, catch up with old friends, have a few nice beers from the local microbrewery, go shopping for things she can’t easily find in Latin America, and catch a couple of poetry nights. She’s considering it a vacation from her vacation. And why would she go to all this expense? While she’s there, she’ll also interview for a place at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine, the next step toward her lifelong dream of becoming a vet.

While Ellen is back in Canada getting her life together, I’m hanging out here near Quito. I wish I could say I was doing some lone adventuring while she’s gone, but instead I’m working on putting to rest those nagging worries that keep me up at night – making a dental claim on my insurance for the root canal in Popayan, getting my taxes done, and putting my banking in order. I also have to decide what to do about my tourist visa in Ecuador – I have three weeks left and need to figure out whether I’m leaving Ecuador as soon as Ellen gets back, or whether I should go on to Peru for a few weeks while she’s gone and try to get back in with a new visa. I’ve been assured that overstaying one’s visa isn’t considered serious here, but I know I’d be uncomfortable being in the country illegally.

My life over the next week won’t be nothing but errands, though. I’m going to take a day or two to explore Quito (first impression – UGLY!), find somewhere inspiring to do some writing, and maybe sit in a park with a sketchbook. I’m tempted to hitchhike somewhere new for a day or two as well, just so I can see more of Ecuador before my visa expires. Guayaquil sounds tempting – I’ve heard that while Quito is the conservative, business-minded city, Guayaquil is the liberal centre of the country. If that means Guayaquil is the San Francisco of Ecuador, I think it might be more up my alley. I haven’t made any plans, though. We’ll see where the wind blows me. And if that means I end up back at the farm in Mindo, that’ll be nice, too.

Occasionally, Ellen and I wonder if we’re spending too much time in one place. We are, after all, on a Latin American adventure, and yet we’ve spent over one-third of our vacation at this farm here in Ecuador. This led me to start an inventory of skills or concepts I’ve learned here.

The largest category of skills I’ve had a chance to develop on this farm have been construction-related. Since the farm is just starting out, there are lots of outbuildings to build and existing structures to expand. Ellen and I have been involved in every stage of construction. We’ve cleared land, felled trees, split bamboo, dug foundation trenches, hauled stones and sand, set posts, built frames, put up roofs, painted, and repaired buildings. We’ve evened the land out, laid a concrete pad, leveled it, brushed it smooth, and kept its surfaces damp while it dried. Then we yelled at the dogs and cats for jumping on the fresh concrete, repaired the scratches and footprints, and re-smoothed the surface. We’ve built greenhouses, drying houses, benches for beehives, chicken houses and barns. Before I came here, I had a feel for the concepts of building, from reading books on construction and from watching building shows on TV, but now I know construction from experience. It’s a different kind of understanding altogether. I can tell by look and feel whether the cement I’m mixing is the right texture and has enough water in it. I’ve never learned that kind of skill from a book.

Despite being a good cook at home, I’ve also learned a lot from spending time in the kitchen here. Cooking here is much more of a challenge than at home because of the availability of ingredients. I have my recipes from home here with me, but they’re completely unreasonable here. My cake recipes, for example, call for half a dozen eggs plus two yolks and a cup of butter in one cake. Here, I cannot justify using any butter or more than three eggs for a cake – we just don’t have the resources. (When the young chickens start laying, we’ll be able to use as many eggs as we like, though.) I’ve learned to cook more by feeling, which I’d heard was difficult with cakes. Just as with the cement, I can tell from texture whether the batter is right. With other dishes, too, I’m getting the feel for how to cook Latin American food. I understand the ingredients and I’m learning how they work together to make the flavours of the foods I love here.

I’m also adjusting my ideas about working with others. When I’m doing projects alongside other volunteers, sometimes I have to let them struggle to do things without stepping in to help. It’s important to let inexperienced people try, and succeed, on their own rather than to do the work myself. Most of the volunteers are much younger than me – between 18 and 23 – and have never done this kind of work before. I’m also working with the family’s daughters, who are 13, 11, and 2, and who are very interested in learning and working alongside the volunteers. I have to let go of my ideas of doing a perfect job, in order to make the project educational and enjoyable for everyone. Even Laia, the two-year-old, gets to have her turn to use a paintbrush or a trowel. I’m much more aware of giving everyone a chance to try, although the work goes more slowly and isn’t done exactly the way I’d do it.

Even with all the things I’m doing and learning, I still have dozens of ideas for things to learn next. Every skill I learn opens the door to other projects for which I’ll need to learn something else. It’s a reminder of how learning is a lifelong journey, and there’ll never be enough time to do everything. Even staying in one place, I feel as if every day is a step in the right direction.

I am constantly surprised, here in Latin America, at how little goes to waste compared to life at home. Prices seem cheap here, but a day’s wage doesn’t go very far, and so people consume exactly what they need and no more. Some people find it hard to adapt to the idea, but I appreciate the change in attitude to waste products.

One example is packaging. At home, when you buy eggs, they might come in a plastic or paper carton, with a full-colour printed label, destined for the trash. Here, eggs are bought by the flat, and when the eggs are gone, the paper flat is used as a seed starting tray, before being composted and returned to the earth. Individually wrapped convenience foods for snacking on the go are also much less common – more often, you’ll see men and women with baskets of fresh-cooked empanadas or steamed corn selling their wares to consumers in a hurry. Nobody seems worried about germs, or the bogeyman poisoning their food – people just buy their food and eat it. Maybe on a continent where the big issues include guerrillas and drug wars, perfectly sanitized and sealed food products are nobody’s top concern. No matter the reason, it’s refreshing to be able to buy a snack on the street without having to throw away three layers of plastic to get at it.

Almost nothing goes to waste on the farm, either. The groceries are bought and brought home in wooden boxes, which are used to store food in the kitchen. Broken ones are taken apart, split into pieces, and repurposed as labels for rows in the garden. When we finish a bottle of cooking oil, the plastic bottle can be used as a plant pot, a weight to hold down the greenhouse roof, or a container for screws, natural bug repellent, or kindling for the fire. Larger empty bottles, if they can’t be reused or exchanged for full ones, are split in half to use as animal feeders. Even little things, like pieces of wire or bent nails, are straightened and put aside for smaller uses. Jam jars, beer bottles, and animal feed bags are returned to the stores that sold them so none are wasted. The family even brings in extra glass jars to the local butter maker, so we don’t have unnecessary plastic containers.

Every activity I do, I’m pleasantly surprised at how little waste I can produce. I get up in the morning, and use the washroom. It’s a composting toilet, so the toilet paper, and its packaging and cardboard roll, all get composted. There is no sewage. The toothbrush, toothpaste, and soap came in plastic which is unfortunately thrown away, but most of the food for breakfast was bought in bulk and stored in reusable containers. The dishes are washed with a biodegradeable soap, which goes through the grey water system and doesn’t harm the plants or the earth. Our projects around the farm produce no waste at all – the cement bags are used as fire starter for the hot tub, and building materials are used repeatedly until they’ve rotted into the earth.

One of the hammocks breaks when I’m sitting in it – the goat has chewed a hole in the side and it tears when he jumps on me. The hammock is put in the free clothing bin, where it is promptly claimed for patches to repair people’s torn jeans and work shirts. People abandon their spare clothing here regularly, and new volunteers are constantly finding they need different clothes for work than they’d packed. Ellen and I have abandoned a few summer dresses and exchanged them for pants and long sleeved shirts. We’re tempted to leave our spare shoes behind as well – shoes are heavy to carry – because we know nothing here goes to waste. Someone will come along who needs an extra pair.

At home, I never thought much about garbage. I put something in a black plastic bag on the side of the street, and somebody takes it away. I never have to see it or think about it again. Here, things are much more visible. There’s no reason to put stuff in a landfill when it can be reborn as something useful. With little access to materials, you’d better make sure you don’t throw anything away that might come in handy later. Quite often when we go into town, the items we were looking for aren’t available, and won’t be brought in for several weeks. When that happens, we’re grateful for the things we saved to reuse later. It’s a lesson that we would do well to learn in North America as well. With too many resources at our fingertips, we value none of them. Here, where buying something to solve your problems is a luxury and a last resort, every last drop of use is squeezed out of every item we own. I hope I can remember that lesson when I leave Latin America, and pass it on to others.

I have never had much to do with horses before. Ellen and I grew up on a farm, but we never raised large animals like cows or horses. Our mum wasn’t fond of any animal large enough to cause serious damage if it lost control, and besides, we were enchanted by the sweet dispositions of goats and pigs. I never felt as if I missed out by not going through the typical teenage girl’s love affair with horses. When we got to this farm, though, we were pleased to note that they had horses here – we could learn more about these popular animals and see what we’d been missing.

That’s what we said when we arrived, anyway. Seven weeks went by before either Ellen or I did more than throw the occasional bucket of food at the farm’s two mares and single foal. They’re pretty enough, but they don’t really do anything. The white horse likes people, and comes running over if you have a bucket of food handy, but the mother and foal mostly keep their distance, and the mother flicks her ears back and stamps her hooves if we even look in her direction. A few volunteers have ridden the horses once or twice in the time we’ve been here, and a couple of times we’ve used them for hauling wood, but most of the time the horses are grazing in the neighbour’s field, and we leave them alone.

Last week, however, a volunteer arrived with experience training horses, and in the last few days I’ve finally had a chance to work with them. In two days, we’ve gone from having to chase the horses around the field to being able to put a halter on without a fuss. Gaëlle showed me how to approach a shy horse without startling it, and I’ve started keeping a supply of horse food in my pockets just in case. I’ve practiced training the horses to walk and stop on command, and I have learned how to tie the horse safely and how a halter works. Learning skills like this, with improvement coming in leaps and bounds, is incredibly rewarding. My confidence with the horses is increasing every day. I’m no longer keeping an eye on their feet apprehensively and wondering if they’re going to kick me – instead, I’m aware of their ears and their mood, and I feel calm and in charge when working with them. I still have a lot to learn, including basics like how to put a saddle on a horse, and I haven’t ridden one in recent memory, but horses are no longer a foreign animal to me. Yet another lesson I’ve learned on vacation that I’d never have thought to seek out on my own.

I don’t plan on going home to Canada when I run out of money to travel. My plan has been to get a job somewhere in Latin America and stay here for a few years. When asked what kind of job, teaching English seems like the most obvious choice: I have a Master’s of Education, I’ve worked six years in the field, I’ve written textbooks on the subject, I enjoy working with learners, and English teaching jobs abound in every major city in the world. The problem is that I don’t actually want to teach in a school. Since giving up on getting my British Columbian teaching certificate a few years ago, I’ve been disillusioned with mainstream schooling. I always loved school myself, but I don’t think it’s the right way to educate people. Much more can be learned by participating in life, without curriculum guides and mandatory testing. How can I get a job teaching in a school, here or elsewhere, when my most valuable learning experiences have been far removed from the classroom?

When I think about the skills and values that are most important to me, I didn’t learn them in school. My passions and inspiration have come from other sources. I adore learning languages, for example. However, I recall being bored in my French classes at school, drawing my amusement from distracting the teacher. We used to play a game, counting how few words in French the teacher could use in a 60-minute period if we diverted his attention elsewhere. Our record was twelve. When I’m teaching English, I don’t look back on my language classes in school as inspiration. Instead, I think of my experiences in Korea, the Philippines, Latin America, and Thailand, trying to interact with people despite language barriers. I remember what strategies helped me express my needs. Memorizing grammar rules by rote, as school language teachers are wont to assign, were never among those successful tactics.

Reading is also a passion of mine. I can devour a book in less than a day, and reread the same novels time and again without getting bored. The books I read in school, though, almost killed that passion. In silent reading in elementary school, we were given twenty minutes to read ten pages of our assigned book. We weren’t allowed to read further than those ten pages, and I was always forty pages into the book before the teacher had seen that I’d gone ahead and told me off for it. I hadn’t noticed the chapter ending – I was too deep into the story. Soon I was reading library books under my desk in class while the teacher was going over material we’d covered the year before. If I was caught, the books were confiscated and the teacher threatened to take away my library card. At home, though, we had thousands of books lining the walls, and I could read any of them well into the night if I wanted, and I often did. I read encyclopedias and dictionaries, poetry and fairy tales, novels and books of cartoons, and when I’d read through all the fiction I started on the books on gardening and cooking. I still read voraciously, but never the kind I was assigned in school. I faked doing my college readings – dry papers in jargon-filled prose written by pompous experts – and bluffed my way through the discussions for them, and yet I read tonnes of books on the same theories, written by down-to-earth real people dealing with the issues. Why does the education system not use these more accessible resources?

When I look back on my life, most of my important lessons were taught outside of school. I learned the value of hard work from my parents, and from working on the farm. The animals needed feeding before we did, because they couldn’t feed themselves. I learned about other cultures from the many volunteers on our farm, as well as from our travels in Europe when I was a child, and my parents’ and grandparents’ stories of living in other countries. The world was a much more exciting place than school ever led me to believe. I remember considering running away, when I was about thirteen, to pursue my dreams without finishing my education. I did my research first, though – I looked through the classified ads in the newspaper to see what kind of jobs I could get without a high school diploma and how much they paid, then compared that to the prices of apartments and airplane tickets. My calculations showed that I’d never be able to make ends meet, let alone save up for trips to other countries, if I didn’t finish high school, so I stuck it out. I don’t ever remember that kind of budgeting taught in school.

Now, as I consider whether to get a job teaching when my travel budget is exhausted, my heart and soul are crying at the thought of spending my days in a school. I’m thinking of the boredom, of the endless assignments and marking, of the curriculum planning of the entire year’s lessons into fifteen minute chunks. I want to teach by being a guide for my students. I want to point them in directions that interest them, and let the students run off their own way, pursuing their passions. I want to be a resource to help people learn. In short, I don’t want to teach in a mainstream school. I wonder, though, where that decision will lead me in my educational career, if I choose to continue it. Only time will tell, I suppose.