You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Written by Ellen’ tag.

Beer is a passion of mine that I hope to carry with me into my career and my farm in the future.

Late in 2011 I found myself the job of my dreams… or at least the part-time job of my dreams. I was working for Paddock Wood Brewing, the local microbrewery in Saskatoon, which makes my favourite brew, 606 India Pale Ale, and was conveniently located just three blocks from my house. When applying for a job there, I wanted to spend more time working in the back, learning the ropes of brewing and bottling, but they hired me for covering shifts in the front of house, so I could only work on the bottling line every once in a while, and they didn’t need or want my help with the brewing. Other unnamed complications prevented me spending my time shadowing the brewers and constantly pestering them about how and why they make the beer the way they do. I satisfied these questions by joining the guys for drinks after work, when there was much to be learned about brewing and beer styles while the boys talked shop.

Actually, I learned the most about brewing from working on Saturdays, when home brewers had a day off their regular jobs and came in to buy malted grains, hops, yeast, and brew kits. They also asked lots of questions that I did my best to answer, and with each discussion I learned more and more about making different styles of beer, like the role of different malts in the brewing process, the flavour profile of different types of hops, the timing and temperature of different stages of the brewing process, and which yeast works best with which style and why. I started out answering most questions based on my limited knowledge and had to turn people away when they wanted specific malts or specific hops. But as I learned more, I began to look up and suggest alternative hops or malts that have a similar flavour profile and can play the same role in the brew. At parties, I found myself talking about nothing but beer, which I’m sure was tiresome for my friends, almost none of whom like beer. I talked beer for hours and hours on end, and was unbelievably happy to find myself working with others who had the same passion for brewing and tasting beers.

I did, however, come to the uncomfortable realization that brewing beer is a process that is almost impossible to do sustainably. There are a few breweries in the States and around the world that aim to be as sustainable as possible, and I’d love to check out their set up to get some ideas for my own future brewery (New Belgium Brewing, Alaskan Brewing Co., and East End Brewing Co., for example) . I have some ideas about how I could do it on an ultra-small scale, even as a business, but the planning would take many years, and it still relies on having access to excessive amounts of water, large quantities of local barley that can be kilned with locally harvested wood (a part of the process I have yet to learn, but am keen to) and local hops that can give me the intense flavour I love in my beer. These things are not impossible to bring together into one place, but I may have to bend my rules and import something for the process. Many brewers and books have told me that malting grains is tricky and not worth the effort when the masters have got it perfected and will sell it so cheaply, and I’m not sure that the hops I’ve seen growing so happily in Canada are very potent. The difficulties with ingredients are one problem that can potentially be solved by trading goods and allowing for imports, but water and energy are the biggest problems in the brewing process.

After more than a year of contemplation, I’m quite sure I can cut masses of wasted water and energy by employing permaculture techniques that take advantage of the heat produced during fermentation, the heat and gas produced while composting the leftover malt that is filtered out of the wort (or from composting the manure from the pigs that eat the leftover malt), by using the hot water as an energy source after the brewing process, and by using a cyclical water system that can filter waste water naturally instead of pouring steaming hot water down the drain and using fresh cold tap-water to heat and cool the wort. This is all a rather lofty dream, but I know that it is possible, with some ingenuity. I’d like to set most of these devices up for my future farm anyways, so putting in the ultra-microbrewery will be a subsequent step in the process, once I’ve figured out how they can work with normal farm waste.

What I’m thinking is that my brewery will really just be for the family, but will produce just enough that my neighbours and friends from the community can have me brew them a keg of beer for their Christmas gathering, or a birthday party, or a wedding. I don’t want to get my name on the market as the best brewer in the world, or have my business grow to compete with the microbreweries that are rampant around Canada and the United States. I just want to bring my community together, to support local and sustainable businesses, and to support community-building events centred around real food and drink produced in the community.

For now, I continue to seek out as many local and interesting beers as I can during my travels and to learn as much about sustainable water and energy systems as I can. Cheers to gaining knew knowledge and tasting new brews!

The new year has me thinking about how absolutely wonderful this past year has been for me.

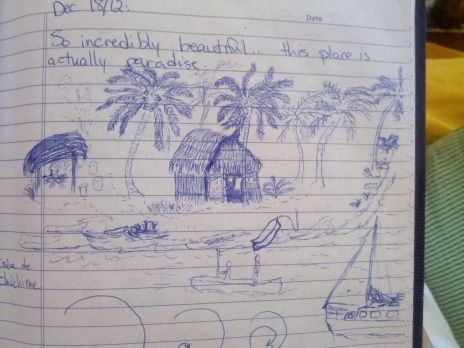

I worked in Saskatoon’s only microbrewery and learned an unimaginable amount about brewing and beer, which has only whet my appetite for more knowledge about beers and brewing. I feel like I passed this passion and good fortune on to my former roommates by getting them involved in Paddock Wood Brewing and its recent offshoot, the Woods Alehouse (if not directly, then indirectly). I became more involved in the poetry community in Saskatoon, and even wrote and performed my first poem (which I haven’t been able to follow up with any other poems, but I’m still enamoured of the first and haven’t been inspired in the same way to write another). Again, I passed this passion on to others by introducing people who I knew would appreciate the atmosphere and beautiful words to the poetry scene in Saskatoon. Through trial (and failure) I learned and shared with others a great deal about different kinds of relationships, learned more about what I want and why, and learned (I hope) another lesson in the importance of honesty and openness in conducting relationships. I discovered that I actually do have a talent for sketching, which I had never believed of myself, through a burlesque and dance centre event shared with a person who taught me many of the lessons I had to learn about love. Now as I travel, sketching has been a way of capturing the people and places I go without relying on memory cards and batteries.

I finished my Master’s degree this year, with a renewed appreciation for my project and the importance of my work. I killed two birds with one stone by spending the spring and summer transforming my thesis into a publication, which meant my hard work will actually contribute to the scientific community, and which also allowed me to save up enough money to travel for as long as I want. I gave away my possessions to various charity groups, and gave my most treasured possessions to the people who I knew would cherish them equally and think of me each time they used these items. I finally started the trip with my sister to Latin America that we have been dreaming of for more than a decade. I’ve learned a huge amount about sustainable farming in the tropics, about renewable energy, and cheap but effective ways to light and heat buildings with little to no energy inputs. I met other travellers who are interested in learning about farming and sustainability, about other cultures, and about local food and community development. I wrote an application to vet school that I feel exceptionally good about, because it truly reflects who I am, what I want to do with the field of veterinary medicine, and how much I have to offer the world as a vet. And I’m continuing to expand my horizons now in the New Year, looking for places where I can learn about natural remedies and medicinal plants that grow here in the tropics.

Almost every day I have had to stop and give thanks for the amazing place that I find myself in, not just physically, but emotionally and mentally. Thanks to everyone who has been a part of this growth over the past year. I love you all and hope you can experience the same wonderful reflection upon your own personal development.

(Hannah’s Note: Ellen and I are on a boat from Panama to Colombia! We wrote a few extra posts to keep you entertained while we are gone – we should be back online on December 22nd or 23rd.)

One of the things I’ve really enjoyed about Costa Rica is the constant communication between drivers using car horns. In Canada, you only use your horn when you have something really important to say. You honk it loudly when someone is about to hit you and hasn’t seen you, or to show your anger at someone who did something stupid like drive into the intersection and get stuck there when the light has changed. Or the old light honk when the guy in front you hasn’t seen the light change. Of course you might toot at friends or someone waving signs on the side of the road, but the horn is something reserved for relatively serious situations, and it’s sort of frowned upon to use it too frequently, or else you might come across as rude. (Typical Canadian thinking, I’m sure.)

Here, you use your horn for absolutely everything. I haven’t spent a lot of time on the road here, but every time I take a bus or get in a car I’m blown away by how many situations call for horn honking here. In San Jose, taxi drivers are renowned for constantly leaning on their horn to convince traffic in general to go faster. They don’t appear to be honking at anyone in particular, just getting out their frustration that they aren’t through an intersection yet or that there is such a long line up to make a turn. Most people don’t go for the loud insistent honking here though, they use a few little friendly toots for pretty much every situation. If you’re overtaking, you honk a bit to let the guy know that he shouldn’t try to pull into the lane. The other driver honks back in acknowledgement. If you’re going around a blind corner, you honk to let an oncoming car know that you’re there.

Motorcyclists honk to let people know that they’re pulling onto the curb to bypass traffic, or more commonly, driving down the middle of the road on the yellow line, honking to let drivers know they’re coming. When the road is too narrow for two cars to pass, and one has to precariously drive into the ditch to let the other by, both drivers honk as if to congratulate each other on a job well done. You honk when you see someone else do something dangerous, you honk to thank someone for letting you in after merging… it just goes on and on.

Of course they also use honking in the same situations that we would use it, but it seems that angry loud honks aren’t really used between cars if a little friendly toot will do the trick.

I’ve never had much worry about what I look like. I feel good when I’m in casual, comfortable clothes, and that’s the most important thing for me. Being on a permaculture farm in the middle of nowhere has now given me even more motivation to make my clothes as practical as possible with what little I have.

With limited resources, a limited budget, and the prospect of a 2 hour bus ride (one way) to the nearest town with clothing stores, I’ve been getting into the typical traveller mode of creating new, more functional clothing by ripping apart and reusing the clothes that I brought with me. So far, my entire wardrobe consists of about ten or twelve items, including socks and underwear. I decided within the first week of being in Costa Rica that my leggings were much more useful as shorts for wearing under a dress, so I cut them to just above the knee. One of my only regrets on this trip has been throwing away the legs instead of repurposing them, but at the time, carrying a handful of fabric with me seemed to be a waste of valuable space and weight. Now that I’m on the farm, that pair of shorts has been the one thing I wear more than any other item. I wear them every day for work in the morning, wash them in my shower if they need it, and then often wear them in the afternoon if we walk down to the waterfalls or into town. I’ve gotten around the issue of underwear limiting the time between laundry days by rotating three pairs of underwear that I wash in the afternoon shower. They dry quickly, usually before I need them the following day or so. I have one pair of socks for working, which I pull up all the way to protect my calves from the rubber boots. They only get washed once a week, but they are just dirty and that’s life. The work shirt has been the most difficult thing to figure out. I was using a tank top, but tight shirts are really not ideal for working in hot humid climates under the blazing sun, and by week two of work I was so itchy I couldn’t stand to wear it any more. Whether that was really from sweat, the tightness, or the rampant fleas from petting the dogs is not entirely clear, but I had to find another solution. I’ve been using my button-up long-sleeved shirt as a cooling overshirt for work, and I love it more than anything else, especially after dipping it into the rainbarrel, which has the advantages of cooling me by pouring cold water down my back, reducing the amount of sweat my body has to produce in order to cool itself, and masking how much sweat my body actually produces while working. I tried wearing it as my only work shirt, but that made it much more difficult to take off and dip in the rain barrel, which I like to do at least two or three times on a hot morning. So, I decided to sacrifice my back-up long-sleeved shirt as my new work shirt. The best thing about this decision is that I now have a lovely loose tank top (wife-beater really) and a really great pair of leggings that is perfect for protecting the area between my shorts and my socks, which had been severely attacked by every mosquito, blackfly, noseeum, and whatever else might have noticed the prime area of soft skin on the back of my knees. I think I look pretty classy with leggings that match my work shirt, but I’ll let you decide for yourself.

Apart from this lovely ensemble for work-days, I have two options for afternoon strolls. I can wear my sarong as a skirt with a t-shirt, or, more often than not, I just throw on my little sundress that I bought when I arrived in Costa Rica. It’s hard to imagine how I could love my clothes any more than I do, even though they are nothing special and they will likely fall apart in a pretty short amount of time given how much I wear them, but I’ve got my sewing kit with me, so I’m ready to take on any repair jobs that come my way. Already on the list is repairing the seam in my shorts which has been steadily creeping up to about mid-thigh, and my favourite sports bra that was already falling apart in Canada is now desperately in need of attention, so I’m repurposing the abandoned clothes from previous volunteers to patch the holes and find a way to keep my leg-warmer style leggings up on my legs instead of slipping down after an hour or two of work. Designing my own garter belt might be the next project, but it’s a little over my head.

It’s been really nice to take a break from trying to impress anyone, to embrace the inner hippy that has always been longing to be fully out there, and to take on new projects that save me heaps of money (or at least a bus trip, meals spent in town, and a few bucks on clothing). With the plan to see how long this trip and my money will last, every penny saved could add up to weeks or months of extra travel time. Taking a hit on the fashion scale is certainly worth the opportunity to explore new life experiences later.

It’s hard to describe the beauty and the magic of permaculture. In a way it is really nothing more than the concept of embracing and using the natural cycles around us to create food while eliminating waste. I’ve been pondering those cycles a lot in this place. The thing about cycles is that it’s hard to figure out the right place to start when describing them. Since they seem to be the most prominent feature in this place, let’s start with the mountains.

This place is nothing but mountains. We’re planting food on ground that is around 45 degrees from horizontal, so the water cycle is of utmost importance. The mountains themselves provide the fuel for this cycle, with hot sunny mornings that bring in cooling rain in the afternoons. To control this onslaught of water, virtually every part of this farm is held together by terraces. We spend the mornings digging ditches that are between one and three feet deep, depending on the plants they support.

Although it is a far cry from easy, there is a certain elegance in the simplicity of digging a trench and using the soil to build a soft fresh pile beside the trench, which then becomes the perfect place to plant yucca and sweet potato. When you harvest the sweet potato, or comote, you pull up the vine-like leaves and stems and follow them to the likely position of the tubers hiding beneath the rich red soil. The roots are harvested using a shovel or a pitchfork, loosening the earth while you go, and the vines are used to replant the mound, after redigging the ditch and adding a bit of mulch or compost to put much-needed nutrients back in the soil, along with protection from the searing sun and thundering rain. Yucca is much the same, except you have to jiggle it out of the ground with your hands, making sure not to pull before you’ve loosened the soil enough to ensure a clean yank. (I hope there are a few of you who are enjoying the rather phallic imagery in this description.) Once you’ve got it out of the ground, you hack off the tough root with a machete and then shove the remaining tree-like stalk back in the soil. How much simpler could it get? The ditch collects water, which feeds the plants which feed us. Which naturally brings us from the water cycle to the intimately connected cycle of nutrients on the farm. You can take any plant as an example, but why not use yucca since we’ve already gone through the harvest and planting procedure, which is of course yet another cycle. With its tough skin, there is a lot of peeling involved in yucca preparation, but this is perfect for feeding the compost pile, while any of the centre that remains too tough to chew after boiling can be fed to the pig. The compost is a mix of kitchen scraps, manure from the cows, chickens, and pig, and dead leaves collected from the many trees around the property. The cows spend the days grazing in the fields, which are dotted with citrus, avocado, banana, and plantain trees along with other trees that are used as wood for building and to attract local species like macaws and monkeys. The cows come into the barn for a snack of freshly cut sugar cane, and leave their nutrient-rich manure as their contribution to the cycle.

Pepe the pig does his part to eat kitchen scraps and contribute to the compost pile. And the chickens of course provide the dual benefits of eggs and manure. They will all likely be a source of meat as well, but for now the meals we eat are mostly vegetarian as they’ve run out of the meat from any previous slaughters. After being turned and tended for two months, the compost is ready to be used for feeding the next generation of plants, and since harvesting and planting are continuous here, the cycle is unbroken. Even the food we eat will eventually add to the fertility of the land, since we use composting toilets here. Again, this relies on a simple design and a moderate amount of labour. All you need is sawdust, space, and time to completely eliminate waste water and chemicals from the process of dealing with human waste. Sawdust is collected from wood that was grown here on the land and then used to build furniture and other structures around the farm. Here they have two bathrooms with two interchangeable chambers. Once one chamber is getting full, you switch the toilet seat over to the second chamber and leave the first to compost over the course of a few weeks or months. Once the second is full, the first should be ready to be emptied, the contents mixed with the other compost and left to finish the decomposition process for another month or two. I haven’t really figured out all the timings for the composting here, so this may be a much faster process than I’ve described. The best thing about this process is that it turns a nasty problem of human waste into an important energy source. Since termites and rot regularly destroy wooden structures on the farm, growing the trees (which have the benefit of attracting toucans) and using the saw to repair and replace those wooden structures is a necessary part of the whole process, so the sawdust used for the toilets is another useful byproduct of this farming method. I could go on and on and on for ages about each aspect of the system, especially the grey-water system, which is one of the most interesting and important aspects of permaculture for me, or the simple insect repellants they make and use from the trees and hot pepper plants… but that`s the beauty of cycles. They just keep going and going and going.

This farm is absolutely wonderful. There are more things that I love about it than I could ever really explain in words, and pictures will only give you a hint of how amazing this place is. I suppose the best way to describe what I’m feeling is to compare it to what I wrote years and years ago on Facebook for my “About Me” section: “I’m waiting for the day when I can put everything I need into one bag on my back, hit the road, and escape society. We’ll build a community somewhere far away in the woods, where we grow what we need, trade for what we can’t grow, and spend the evenings making music and laughing around the fire.” I feel as if I have actually achieved this goal that I created for myself more than five years ago. Ok, we haven’t sat around a fire yet, and we haven’t replaced money with traded goods, but other than that, this is precisely what I wanted to find.

The sense of community is something that has been the most important thing I have been seeking. This place certainly has it. We arrived by bus on Sunday evening a week ago, getting off in the dark on the side of the road and hoping that the farm was indeed at the top of the hill as the bus driver and a helpful American passenger assured us it was. When we got to the top of the hill, we were greeted by a table of seven volunteers, six of them from the United States (the term “American” is much frowned upon in Central America, since they consider all North, Central, and South Americans to be American) who were speaking in rapid Spanish. I immediately felt a wave of relief mixed with anxiety. These volunteers were serious about learning Spanish, so it was certainly the perfect place to immerse ourselves, but we could barely string a sentence together between the two of us. Over the course of a few days, we’ve been steadily expanding our vocabulary with incessant “¿Como se dice ___?” and “¿Que significa ___?” questions.

The other volunteers have been absolutely wonderful, and I know it will be much harder now that every single one of them has moved on, leaving Hannah and I with the family, who speaks only Spanish and the odd English word or two, and an intern, Nick, who has worked here each winter for three years. His Spanish is an intriguing blend of Spanish words pronounced with a distinct American lilt and English words pronounced with a slight Spanish accent. For example, the sweet potatoes grown here are called “comotes”, which he happily pronounces the way we would pronounce “coyotes”: something like camodees. His total lack of concern about knowing the correct verb tense, pronunciation, or even the correct word itself has made me more confident in speaking without worrying about what it sounds like, but I will miss the lessons in grammar and translation that the other volunteers provided. My Spanish is coming along quite nicely, despite my tendency to use German grammar, and I can’t wait until the new volunteers arrive so that I can have a conversation partner who is further along in learning than Hannah or I, since I need to look up most words that I want to say. I find it difficult to understand Javier, who is the incredibly friendly host who jokes and teases with ease, but doesn’t slow down much for the volunteers whose Spanish is rustier than the others. His wife, Raquel, is also really kind and an amazing cook, but I find her rather shy and I never know quite what to say to break the ice.

Anyways, back to the sense of community and the farm itself. We spent the last week working hard in the mornings on various projects and then relaxing in the afternoons and checking out the local waterfalls and national park. We cook in a community kitchen and decide what to make based on the leftovers and the fresh fruit and vegetables that we grow here on the terraced hillsides. What I’ve loved about sharing this experience with other volunteers is the support we’ve all had and given in the process of learning Spanish. The dictionaries that are always on the tables are constantly being perused by the volunteers, and we discuss the words we find or how to conjugate them in various tenses. Everyone has a journal-type notebook that they write in regularly with memories of the farm, useful words that they learned, contact information of other volunteers, doodles and sketches, and even glued in pressed butterflies, leaves, and flowers. My own journal has been much more neglected, but I’ve been filling the back pages with words, phrases, and verb tenses, and I’ve even attempted to translate the entries that I’ve already made into Spanish. I gave up on that when I realized that it was probably ending up like the essays written by Hannah’s students who wrote the entire thing in Korean and translated them word-for-word into English using google translate – not really the best way to learn how to use a language.

I think the type of people you find doing this type of volunteering will always be the kind who want to experience a community, to share ideas and skills, and to maintain a positive atmosphere. I’m glad that the people we’ve met so far have also inspired me to continue exploring my spirituality and maintaining a Zen-like state of being happy to be alive and experiencing each moment. In any case, with Hannah keeping the world up-to-date on Facebook and the blog, I feel quite comfortable to take a long break from the online world, now that I’ve finished my application to vet school. I will likely keep doing the odd blog entry or post on Facebook, but I find that I don’t really want to be perusing the internet when there is so much here that I have yet to discover and so many words that I need to look up and write down. So if you’re feeling abandoned without updates, just know that I think of all my friends in Canada and around the world often, that I wish you could all come here to experience this with me, and that I will send you a postcard or a letter if you gave me your address via email or Facebook. I can’t promise when or from where, but I will keep in touch eventually.

So this is my attempt to provide an alternate view of Puerto Viejo than the one written by Hannah. In all honesty, I fell in love with Puerto Viejo eight years ago when I missed out on it due to a poorly planned lack of food and abundance of alcohol and marijuana, and it’s hard to change a first impression. I loved Puerto Viejo from first sight, with its sparkling coastline and slow-moving Caribbean pace. The streets are full of locals and tourists on bicycle or on foot, with the majority of motor vehicles being shuttles rather than private cars. I love that everyone greets each other on the street and locals are happy to point you in the right direction if you have any questions. The town is small enough that you recognize the same faces day after day, with a constant flow of tourists coming and going through the town. Staying at Rocking J’s Hostel was fun, although I had my doubts in the first day or two. We arrived on a Tuesday, which is a fairly slow day at the hostel, so there were only about ten or fifteen people there, rather than its maximum capacity of around 250 spaces (99 hammocks, 99 tents, and 30 or 40 dorm rooms). The thought of it being full in the peak seasons like Christmas, spring break, or summer is totally overwhelming. By the weekend, there were closer to fifty people at the hostel, although it fluctuates so much it was hard to tell.

I have to say, the hostel improved with the passing of time. I liked the way new travellers arrived and were accepted into the groups that formed, cooking meals together and sharing the cost of food, beer, and rum. Hannah and I had to be careful about sitting around the table when they brought the pot of food out, or we ended up with a plate of food and a bill for our portion from the person who purchased the supplies.

As a lover of languages, I couldn’t stop listening to the mishmash of languages being thrown around the dinner table. Most hostellers were speaking English as a common language, but there were always little side conversations in Spanish, German, French, Swedish, or Norwegian, as those whose English was less than perfect required an explanation of a word or an idea, or simply a private moment without being overheard by others.

One of my favourite things was listening to the conversations between hostellers with different levels of Spanish. Sadly, most of the native English-speakers hadn’t bothered to learn Spanish regardless of how long they had been travelling in the region. They always blamed the eagerness of locals to practice English and suggested that there was no need to learn Spanish if one spoke English. It is totally hypocritical of me, but I always felt a little surge of pride in these moments; I knew that I was going to learn Spanish and so I had the right to feel superior, despite speaking barely a word of Spanish all week, much less conducting an entire conversation.

But it was great to listen to the French-Canadians switching with ease between Spanish, French and English. It reminded me of the times I needed to explain something in German because I had only ever learned the vocabulary in German, or the times I acted as translator for Hannes, who spoke with such a strong Swabian dialect that the Bavarians he was studying with couldn’t understand what he was trying to say. At any rate, hearing the Germans and French at their various stages of learning Spanish was encouraging, since you can imagine what your Spanish might sound like in a few weeks or a few months.

On our last two nights we discovered the fire pit, which appears to be an attraction that the hostel offers its guests, as the fire and wood materializes by nightfall without any sign of the person who starts it or collects the wood. Fire is something so uniquely human, and like music it is a binding force across all nationalities and languages. Sitting around the fire with drums, guitars, and an accordion, groups of people from around the world share a common language that we all connect over. Of course, I preferred the traditional folk songs from other cultures, and I was slightly disappointed that the majority of songs sung around the fire were American or British pop songs instead of folk songs, but the world is a small place now, and Rocking J’s is certainly the epitome of an Anglicized Caribbean culture.